The Church is an increasingly marginalized, and in the view of many, irrelevant institution in western culture. The Christian mindset no longer dominates and informs the imaginations of people in our society as it once did. When I join the guys for a beer after we play hockey once a week (a major reason for playing hockey in the first place!), I always have this deep sense of entering a different universe. It’s a universe that hasn’t just rejected God, he never existed in the first place. When my hockey friends asked me about what I do, they listen politely, but I can tell from the glaze in their eyes that they think I come from another planet. It doesn’t take long for our conversation to turn to other matters: ‘Bartender another beer please’!

My sense is that I’m not the only Christian experiencing this feeling of displacement and uncertainty living in today’s culture. As an Anglican priest, I am particularly occupied with how the Church can reach out to share the Gospel with people just like my hockey friends. How can we engage a culture whose imagination and thinking are so far from a Christian understanding of the world? Admittedly, I’m not sure what to do. But I do think we need to start with understanding why the default position of the majority of people today is disbelief in, not only the Christian God, but in any deity. Why is it natural for our friends, neighbors and even family members to not believe in God?

For an answer I’m going to draw some help from Canadian Philosopher, Charles Taylor, and his book ‘A Secular Age’[1]. According to Taylor, the secular age we live in is conditioned by an ‘immanent frame’. That is to say, people assume that what we see in this world is all that there is. It doesn’t even enter peoples’ minds that meaning (i.e., questions of right/wrong, what’s the point of life and what does it mean to have a good life), can be found beyond this world in a transcendent force or God. Therefore, the world is no longer ‘enchanted’. We no longer believe in silly things like miracles, angels, the devil, that God created the universe, or in divine revelation. Whereas 500 years ago atheism was unimaginable, today belief in a Christian God (or any other God for that matter), is unimaginable

Accordingly, the Christian story is not the only story in town. Christians live in a cultural space in which many secular stories compete with our story. These secular stories are delivered in many forms and places: shopping malls, commercials, hockey rinks, coffee shops, government policies etc. These competing stories are so much in the air we breathe in today, we’re most often not even conscious of their impact on what we think and feel. Flannery O’Connor summarizes this struggle in a letter she wrote about her first novel:

I don’t think you should write something as long as a novel around anything that is not of the gravest concern to you and everybody else, and for this is always the conflict between an attraction for the Holy and the disbelief in it that we breathe in with the air of our times. It’s hard to believe always but more so in the world we live in now. There are some of us who have to pay for our faith every step of the way and who have to work for it.[2]

Notice what O’Connor says. We may be attracted to the ‘Holy’, but ‘disbelief’ permeates our faith in God because it’s what we ‘breathe in our times’. Therefore, it’s becoming harder and harder – even for Christians – that Christianity is believable in today’s age. The difference between our modern secular age and past ages is not necessarily that there is a catalogue of available beliefs but rather the assumptions we hold about what is believable.[3]

But that does not mean the humanist, atheist or agnostic is not haunted by stories of the transcendent or God? That’s why atheist writer Julian Barnes says, ‘I don’t believe in God, but I miss him’.[4]He doesn’t believe in God, but yet he is haunted by God. Or consider Walter Isaacson’s recollection of what Steve Jobs said when he was dying in his biography:

I’m about fifty-fifty on believing in God. For most of my life, I’ve felt that there must be more to our existence than meets the eye. I’d like to think that something survives after you die … I really want to believe that something survives, that maybe your consciousness endures. But onthe other hand, perhaps it’s like an on-off switch. Click! And you’re gone. Maybe that’s why I never liked to put on-off switches on Apple devices.[5]

There continues to be fleeting moments of something more for people. That’s why the magic of Tolkien’s, ‘Lord of the Rings’, or of the ‘force’ in Star Wars still captivates wide audiences.

Still, today’s secular age is predominantly influenced by exclusive humanism. It forwards an understanding of the world that assumes spiritual forces, angels or God no longer exist. We now assume to live in a ‘closed world system’, says Taylor, in which what’s right and wrong and the meaning of life has no room for God. For example, on a recent CBC program I was listening to, a scientist argued that (and I’ve heard this theory from my secular friends too), ethical questions can only be answered by evolutionary science and gene theory. The advancement of our species as mapped out for us in gene theories are what drives every ethical decision we make. That God and a divine order of nature can inform what we do is not even on the radar in today’s secular imagination.

Now that the Christian story is contestable and just one of many stories for mapping out our understanding of life, individuality and the power to choose informs who we are, not community engagement and practices such as can be found in the Church. In the words of Jean-Francois Lyotard, ‘Contemporary society no longer speaks of fraternity at all, whether Christian or a republican. It only speaks of the sharing of wealth and benefits of “development”’[6]. In other words, we are ‘liberated from every other, from obligations of human community, from anything that impinges on the project of ‘The Big Me’[7].

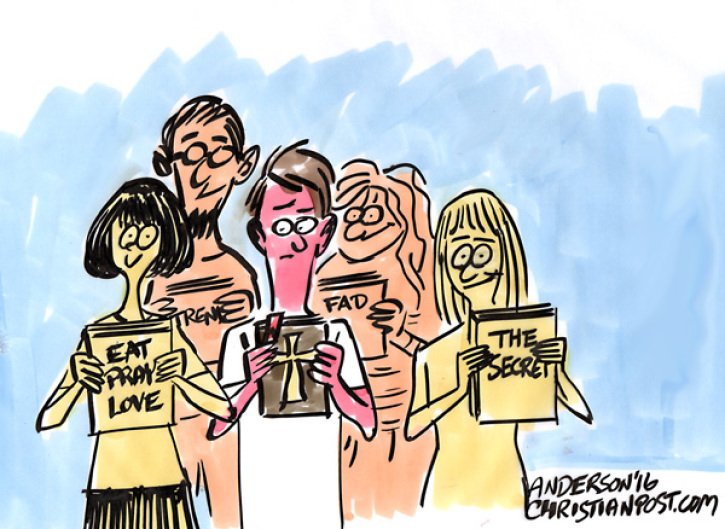

Many Christians are influence by this ‘Big Me’ mentality. Christians, just like everyone else in our society, see themselves as consumers who look for churches that will give them the type of worship and the programs that will best advance what ‘they think’ is spiritually best for them. In response, many churches, in the name of being ‘relevant,’ have moved away from their traditional forms of worship (some even worship in pubs now!) and, try to offer programs that people want.

The problem with this approach to the Church is twofold. One, there may be some numerical success in these churches, but membership is very fluid. It doesn’t take long for people to feel like they are not getting exactly what they want and so they move on. And two, the true God as revealed in Jesus Christ is not a consumer item. The God of the Gospel is a jealous God who will have no other gods before him, including the God we imagine best meets our spiritual needs.

So, what do we do? First, we need to understand that we are primarily desiring creatures who are always seeking to love someone or thing. Whatever we ultimate desire and thus love will shape who we are and what we do. Second, our desires, and thus what we love, is primarily shaped, as I’ve already alluded to above, on a subconscious level. On the most part, we are not consciously aware of the different stories in our secular age that are shaping our desires and what we love. Third, the way the stories of our secular age shape our desires are through their habit-forming practices. Every time we engage in the practice of listening to the CBC, shopping in a mall, watching TV (especially commercials!), going to school and work, attending a sporting event, or spending time in the local hockey rink, our desires are being shaped and thus, so is what we love.

Now, I am not suggested we remove ourselves completely from the influences of this secular age, as some evangelicals think we should do by going only to Christian schools and listening only to Christian music. First, even if your try, you can’t avoid society completely and second, there is much that is good in the world. But what we can do, so that our being-in-the-world is not totally shaped by secular stories is recommit ourselves to Christian practices as mapped out for us in the life of the Church. Since our imaginations are contested, being pulled, wooed and shaped by competing stories about the ‘good life’ from our culture, we need to engage in regular Church practices, so that the Christian story shapes our desires and thus direct our ultimate love and service to our Lord, Jesus Christ.

Remember, disciples of Christ are made, not born. Disciples are formed when their imaginations are conscripted by God and that can only be done in and through committing oneself to the practices of regular worship, regular reading and study of the bible, serving on committees, a daily prayer life, belonging to a cell group, ministering to the sick, needy and poor, etc. Our desires and imaginations need to be sanctified by the Holy Spirit so that our desires rest where they should rest, in Jesus Christ. But that can only happen when and if we engage in these Church practices. Because if you don’t, secular stories and their habit-forming practices will shape you heart, soul and mind whether you like it or not

[1]Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, Belknap Press, 2007).

[2]Cited in James K.A. Smith, How (Not) To Be Secular: Reading Charles Taylor, p. 11.

[3]Ibid., p. 19.

[4]Julian Barnes, Nothing To Be Frightened About Of (London: Jonathan Cape, 2008), p. 126.

[5]Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2011), pp. 570-71.

[6]Lyotard, Political Writings, trans. Bill Readings and Kevin Paul German (Minneapolis University of Minnesota Press, 1993), 161.

[7]David Brooks, The Road to Character(New York: Random House, 2015), chap. 10.